ADF Serials Newsletter

For those interested in Australian Military Aircraft History and Serials

ã 2003

July 2003

In this issue:

Editor’s blurb: Hi everyone. This edition of the newsletter is packed with a range of articles. Gordon continues his investigations into the P40’s with part 3 of their story. Jose Cordoba, a new team member, gives us an insight into how he became involved in aviation history. Jose and Grahame have been working on the crash site web pages and have a new crash site for you to access. Dean continues his series on aircraft accident reports with the loss of a Lincoln at Amberley in 1948. Additionally, I have included a section on the loss of A9-225 on 12 July 1943.

This month we provide the opportunity for newsletter subscribers to purchase images held by the ADF-Serials group. Please check out the site below.

A new feature this month is the inclusion of Department of Defence media releases on relevant research interests. This month we have included a media release on the funeral service for a Lancaster crew in Berlin. For those who would like to learn more about this crew, there is a link to a website contained in the release.

Until next month,

Jan

Images Auction – ADF Serials

As most of our readers are aware, the ADF Serials website is maintained by a large number of volunteers who generously donate their time and skills. However, like all voluntary organizations we also have expenses. ADF serials are currently auctioning some aircraft images with all proceeds going to the ADF-Serials website. If you would like to see the images, please go to:

http://www.adf-serials.com/auction/

Crash Sites:

Well the response to this section of the website has been fantastic with over 750 hits in 5 weeks! Congratulations Grahame and Jose - not bad for a new web page. This month a new page has been added with details of US Navy R4D-5 (C47) Blue Goose crash in WA, which can be viewed at Crash, sites web page at:

Our ADF-Serials Team – Jose Cordoba

I am 36, married with four kids and work as a rigger on construction. I was about five years old when a mirage flew low-level right over my head, and that started an immense interest on military aircraft.

I've done some flying in piper tomahawks for my private pilot’s license (10 hours) but ran out of funds. Once the kids stop eating I will fly again. I am a mad keen fisho but I will always look up to see what is flying past. I live right next to Illawarra regional airport and Hars has moved in, so no lack of interesting aircraft around here.

Heard about a crashed bomber on Bong Bong Mountain, and started to look into that story and with it found another 8 air wrecks in my area. Over the last year I have climbed all over these mountains and have managed to visit the sites of 3 aircraft. I am not a souvenir hunter and only take photos leaving the wreck sites in peace.

Early USAAF P40E/E-1 Operations in Australia Part 3 – Gordon Birkett

The P40E represented the first modern massed produced fighter that the RAAF had at that time, to carry the fight to the then relentless onslaught by the Japanese up to March 1942. Up to that time, apart from Brewster Buffaloes operated in Malaya in forward defense by 21 and 453 Squadrons, Australia had no front line Fighter aircraft equipping its airforce on the mainland of Australia. History written in Australia to date has largely omitted over this period from December 1941 to March 1942, the true story of the number of P40E fighters that were landed on our shores, formed into Squadrons and sent off to fight the Japanese.

Background

It started when a reinforcement convoy to the Philippines left San Francisco between the 21st and 24th November 1941. This convoy, named after its escort, the USS Pensacola, consisted of the following ships:

Aircraft Ownership

The parent Unit of this shipment, the 35th Pursuit Group, made up of the 21st (equipped withP40E’s) and the 34th (equipped with P35A’s) Pursuit Squadrons, was to be the second P40E Group to be based in the Philippines after the 24th Pursuit Group (3rd, 17th and 20th Pursuit Squadrons). These 18 P40E’s were to be used to initially equip the 34th Pursuit Squadron, based at Del Carmen Field, with its replaced P35A’s being the initial equipment of the 70th Pursuit Squadron, which would arrive from the states after December 1941.

During this work-up, the 35th Pursuit Group Squadron’s command was assigned under the 24th Pursuit Group. This arrangement continued at the start of the hostilities on the 8th of December 1941, Philippine time, till attrition resulted in only one squadron size force surviving.

The Convoy’s new Destination

Due to the supremacy of the Japanese Navy at this time, and its resultant blockade of the Philippines, it was considered at that time to change the destination of the Pensacola Convoy to Brisbane, Australia.

The reason behind this was twofold. Firstly, there was thought at that time that there were ample facilities for the assembly and training of these reinforcements, without the chance of attack. And secondly, they could be air ferried across Australia, via Darwin, Timor, and Borneo to the Philippines, thus bypassing the Japanese naval blockade. This Route had been laid out as a backup, some months before by General Brereton, as a way of reinforcing the Philippines, should the enemy enforced a blockade. However, the primary idea was that this route was for bombers, with sufficient ferry range. However it was realised that the P40E, with a drop tank, could negotiate the route. The result would then be landing combat ready P40 Pursuit Squadrons to reinforce beleaguer fighter forces, then holding back the tide of the Japanese thrust.

The Arrival and its Destination

The Convoy arrived in Brisbane’s Newstead Wharves on the 22nd December 1941 with it’s eighteen P40E-cu’s and fifty-two A24 Banshee’s (Army version SBD3 Dauntless Dive-Bomber) for unloading and then for assembly. These aircraft were trailed to the new Amberley Airforce base outside of Ipswich, some 60 kilometres away. For erection and assembly, disembarked USAAF personnel from this convoy, along with the volunteers from the AVG contingent on route to China via India, commenced the job of unpacking these aircraft from their crates. RAAF personnel from No 3 S.F.T.S (Service Flying Training School) assisted in the assembly of these P40E aircraft, along with USAAF Personnel of the 8th Material Squadron (7thBG) and 75 AVG volunteers from the SS Bloemfontein. Their assembly of these eighteen P40E’s was completed by the 9th January 1942.

Despite several problems, including the supply of coolant for their radiators and the lack of a rudder for one of the aircraft, training commenced. Because of the nature of its destination, to reinforce the existing fighting units in theatre, the Unit was designated as the 17th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional). Additional pilots evacuated from the Philippines joined the unit.

.

The Serials of the first Eighteen P40E-cu Warhawks in Australia of the 17th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional)

After researching USAAF Aircraft data cards, particularly their shipping dates and arrival dates, and photographic records and assistance from co-researches, the following serials are those of the eighteen:

FY Serials: 40-662,40-663,40-666,40-667,40-670,40-671,40-674,40-675,40-678,40-679

41-5305,41-5314,41-5332,41-5333,41-5334,41-5336*, 41-5337,41-5338

What’s interesting is that one of the above was latter taken over by the RAAF sometime during March 1942. It is believed that this one was a repaired P40E in transit to Java, or the one left behind at Amberley minus its Rudder. (More research has determined that this P40E, FY Serial, 41-5336 aka A29-28, was the Hanger Queen left behind at Amberley, then used for training by 3SFTS RAAF.

A29-28, aka 41-5336, at RAAF Amberley late March 1942. Note the standard Olive drab finish. C.Bushby.

The journey north

The squadron was ready to deploy by the 16th January 1942. However by then, the Philippine air route had been severed by this time at Borneo by advancing Japanese Forces. It was therefore decided to reinforce USAAF forces in Java with the intent to re-open the route when sufficient forces, then on their way from the USA, would allow it.

They left Amberley in two flights, one of nine P40Es led by a C45 flown by Capt "Pappy" Gunn and one with eight P40Es lead by two RAAF Fairey Battles to Rockhampton as part of their first leg. All arrived, however one crash-landed by 2nd Lt.Carl Geiss, (40-663) which resulted in the force being reduced to sixteen P40Es. Following refueling, the Squadron flew onto Townsville for an overnight stop. Here another aircraft (40-667) was damaged on landing. The following day, the squadron flew onto Cloncurry and then onto Daly Waters for another overnight stop.

The following day, the 19th January 1942, they landed at Darwin. Here they waited for several days pending maintenance staff, who were flown up by RAAF DC2s to service the aircraft and for one of the Veteran Philippine pilots (1stLt.Gerald McCallum) to recover from illness. They departed for Java on the 26th January 1942 from Darwin, where they came under ADBA Command for the defense of Java.

With minimal loss, the route had been proven that P40Es could be air ferried to reinforce USAAF Forces in the Far East. With the arrival of more than 55 P40Es, some four days earlier prior of their departure, on the SS Polk, reinforcements were starting to arrive.

These were to follow the 17thPS (Provisional), as you will see in Part 4

Credits: C "Buz" Bushby, W.’Bill’ Bartch, and Peter Dunne

Update on Canberras – Bob Livingstone

Martin raised the following issues re the recent Canberra story in the newsletter. The discovery of the reports in Flightpath Vol 1 No 4 re the scrapping of Canberras A84-216, 221, 222 and 224 have raised more questions than answers. For starters what where these aircraft previously based at Amberley doing at Morwell in the old gas factory in the first place? Who owned them? (Peter Hookway?), how did they get there? (via Essendon?). Did they make a final ferry flight or were they trucked? Does anyone have details of their demise or better still images?

Bob Livingstone raised the valid issue that the Canberra’s would still have been airworthy in 1972 so they didn’t fly them down. If you know any further information on this, please use our feedback page

On This Day ….

2 July 1950 – 77 Squadron flies first combat mission in Korea (First Australian unit committed to the Korean War)

12 July 1943 – Loss of A9-225 shot down by a US Navy Liberator near Rabaul – see following article

27 July 1953 - Signing of Armistice to End the Korean War

On 25 June 1950, the outbreak of the Korean War, attributed to North Korean troops crossing the 38th parallel into South Korea, saw RAAF aircraft and personnel quickly involved in the fierce conflict. 77 Squadron, equipped with Mustangs and based at Iwakuni in Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), were ready to return to Australia when they were committed to operations in Korea. The squadron flew their first sorties in the Korean War on 2 July 1950. It soon became obvious that the Mustangs were no match for the Soviet MIG-15 aircraft that entered the conflict in November 1950. By April 1951 when the Mustangs were withdrawn from service, 14 had been shot down by enemy flak. A decision was made to re-equip 77 Squadron with jet fighters, the Bristol Meteor 8. While undergoing retraining from April – August 1951, five aircraft and two pilots were lost in flying accidents. By December 1951, despite the obvious skill and bravery of the Australians, it became clear that the Meteor was no match for the MIG in battle and fearing heavy losses, the UN air force command withdrew the Meteors from interception operations and the squadron focussed solely on ground attack. Despite this change, the losses of 77 Squadron aircraft continued and as the shortage of skilled pilots grew, the tour of duty was reduced to 6 months (from 9) and RAF pilots boosted the squadron numbers.

By the time the armistice was signed on 27 July 1953, it was estimated that 5 machines were lost during battles with MIGs, 20 by flak, 13 lost in accidents and 7 seriously damaged in air battles.(Sources: Odd Jobs: RAAF Operations in Japan, the Berlin Airlift, Korea, Malaya and Malta. 1946-1960). Approximately 2,000 RAAF personnel had served in Korea and Japan during the Korean War. Of these 28 were flying battle casualties, 13 accidental deaths (9 flying accident casualties, 3 ground accident casualties, 1 death by illness and 6 were taken prisoner of war. There are no statistics available for RAAF wounded. (Source: http://www.awm.gov.au/korea/glossary.htm)

Australia’s involvement in the Korean War, the first major hostile action of the Cold War, signalled a closer alignment with the United States, an alignment still evident today. Many pilots who served with the RAAF during the Korean War, were an integral part of RAAF senior management in the 1960’s and 1970’s including Ray Trebilco, Ron Susans and Bill Collings.

The Loss of A9-225, 12 July 1943 - Jan

On 12 July 1943, the crew of 100 Squadron Beaufort A9-225 based at Gurney Field, Milne Bay failed to return from an armed reconnaissance mission near Bougainville. The following morning a message received from the US Navy stated that it was believed a US Navy Liberator (PB4Y) had shot down an RAAF aircraft near Rabaul. Extensive search and rescue efforts located the surviving three crew of the Beaufort on three occasions but were unable to pick them up. After the last sighting on 6 August 1943, the crew were never located again. . The families, although promptly notified that the crew were missing in action, would wait until July 1947 before the crew were officially declared dead on or after 12 July 1943. It would not be until almost 60 years later that the families would find out more about the incident from a US Navy Incident Report. Unfortunately, the report did not shed any light on the crew’s fate after being shot down and thus, the cause of their deaths will never be established.

The crew of A9-225: Flying Officer John Clifton Davis (pilot), Flight Sergeant Geoffrey Raymond Emmett (observer), Sergeant George Collins and Sergeant William Thomas Brain (Wireless Operator/Air Gunners), completed their preliminary training under the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) at specialised units. On completion, they were posted to 1 Operational Training Unit (1OTU) at Bairnsdale. Twelve crews were formed and commenced No 7 Beaufort (T) course on 5 January 1943. The Beaufort, intended to serve mainly on longer-range shipping strikes, anti-submarine patrol, and convoy escort duties, was mainly involved in close support/attack work had developed a notorious reputation owing to the large numbers of accidents during training. Accidents on take off and landing were common, although fortunately many crews walked away from the aircraft with minor injuries. Others were not so lucky. In the period between January and March 1943, twenty-three aircrew (22 trainees and one instructor) were killed in flying accidents at No 1 OTU including the crews of Sergeant Douglas Connell and Pilot Officer Herbert Greenwood from No 7 Beaufort course.

After completing the conversion course to Beauforts, No 7 Course were posted to Base Torpedo Unit at Nowra for torpedo training. Most pilots who graduated from the demanding and dangerous course later stated that it represented the most hazardous period of their wartime flying as crews practiced low flying over the sea to avoid being picked up by a ship’s radar. On approach to a target, they would fly as low as 10–20 feet and climb to 150 feet to drop the torpedo.

No 7 Beaufort course spent an eventful time at Nowra. High unserviceability rates, bad weather, sabotage attempts and accidents hindered flying operations. No 7 Course lost four members during their training at Nowra. On 12 July 1943, Flight Sergeant Wiggins’ crew crashed during a training flight resulting in the death of Sergeant Cyril Jackson while on 24 May 1943, Sergeant Geoffrey Parker’s crew crashed into the sea during a simulated torpedo attack, resulting in the death of all the crew except Sergeant John Perrin. Fatalities were not limited to trainees at Nowra. On 14 April 1943 during a formation demonstration for war correspondents, two experienced Beaufort crews comprised of instruction staff at BTU, died when their planes collided during the demonstration.

There was evidence on 17 April 1943, that six Beaufort aircraft had been sabotaged and all aircraft were grounded for inspection. The situation worsened two days later when the personnel at BTU were informed of another sabotage incident. All aircraft were grounded pending inspection of control cables after tampering of rudder controls on four aircraft had been discovered. From the last week of April until the end of May, training was interrupted by poor weather and No 7 Course were sent on short leave, as the airstrip was unserviceable. By the time No 7 Course completed torpedo training their total flying hours were 249, much lower than any other course.

Despite this, during training, No 7 Beaufort Course had suffered a 23 percent fatality rate, above average for Beaufort crews. Ironically, the members of No 7 Course would never drop a torpedo in operational service. Shortly after they completed their course, it was decided that the newly formed No 8 Squadron would perform all torpedo operations.

All graduates of No 7 Course were posted to 100 Squadron at Milne Bay and arrived there around 13 June 1943. After completing a flying check on 26 June 1943, Cliff Davis and his crew were cleared for duty and their first four operational missions included armed reconnaissance patrols and an anti-submarine patrol. On 12 July 1943 at 9.53 am, Cliff’s crew set out in Beaufort A9-225 on another reconnaissance mission of patrol area, ‘R1’, which took them close to Rabaul and Buka Passage, the strait between the islands of Buka and Bougainville. They were scheduled to return at 3.30 pm. When the aircraft was 45 minutes overdue, a coded message was transmitted asking the aircraft to give its estimated time of arrival. The aircraft was called at intervals until 7.56 pm by stations at Milne Bay, Moresby, Townsville, Vivigani, Horn Island and Cairns with no acknowledgement. At 3.45 am the following morning, the squadron received word that a South Pacific (SOUPAC) aircraft had sighted and shot down an unidentified aircraft at 0630S 15402E at 1.02 pm the previous day. The aircraft crash-landed into the sea and two white men were spotted in the water. A life raft with flares and food was dropped. A Catalina was diverted to Milne Bay to assist with the search and all friendly submarines were asked to keep a lookout for the crew. The delay in advising the RAAF of the downing of the plane would have serious consequences as the search had to be temporarily abandoned due to bad weather.

On 20 July 1943, after receiving a report from an unspecified source, a crew from 100 Squadron spent almost nine hours conducting square search patterns for the life raft with no success. On 1 August 1943, a 100 Squadron aircraft piloted by Sergeant Hay, while on routine patrol, reported seeing three men in the raft but lost them almost immediately in bad weather. Intensive searching resumed with no success until 6 August 1943, when Sergeant McKenzie and his crew spotted the life raft and reported two of the crew alive and active and the other one under a canopy at the back of the raft. Due to extremely bad weather and poor visibility, the raft was lost almost immediately. Square searches were immediately carried out in continuous rain and at times, almost zero visibility. The aircraft stayed as long as possible until their fuel levels were critical and abandoned the search with great reluctance.

Searching resumed the following day. 100 Squadron members flew in marginal conditions and on occasion had to land at other locations including Vivigani, on Goodenough Island. However, despite the extensive searching the crew were never located and were posted as missing in action. After the cessation of hostilities, Japanese Prisoner of War Records were examined for information regarding the fate of missing Australian crews in the Pacific region. A thorough search was made of the Louisiades, Woodlark Island, Marshall–Bennett, Laughlan and Alcester groups for the crew. Despite these extensive enquiries, no further information was obtained on A9-225’s crew. As the identity of the three survivors could not be ascertained, on 1 July 1947, it was decided that all crewmembers would be declared to have died on or after 12 July 1943 with drowning as the most probable cause of death.

In 2001 when researching the story of my great uncle’s crew, I was fortunate enough to make contact with two American researchers, Jim Sawruk and Harry Brooks who were able to supply additional information including the action report from the US Navy plane, a PB4Y from VD-1 Squadron based at Guadalcanal. A Zed Patrol as flown by the PB4Y, flew to Bougainville and then 75 miles toward New Guinea and returned. This meant that it overlapped the reconnaissance areas flown by the Australian crews operating from Milne Bay. At approximately 1.08 pm the PB4Y spotted a Japanese Betty aircraft which pulled away in the direction of Buka Passage but the range was never close enough to fire. At 1.15 pm a two engine plane was observed flying low over the water towards Buka Passage and the PB4Y dived on this plane. The other plane sighted the PB4Y and turned directly towards it. At a range of about 1000 yards and altitude of about 100 feet, both planes fired. The waist gunner and tail gunner on the PB4Y saw splashes in the water indicating fire from the other plane and the top turret and bow turret of the PB4Y fired. The Beaufort made a sharp right turn about 500 yards distant and pulled away rapidly out of range. The PB4Y chased the plane for about 10 minutes before observing the other plane catch fire, make a 90-degree turn to the right and land on the water. A life raft with additional supplies was dropped and the crew observed two of the survivors clambering into the raft. The PB4Y reported the incident and remained in the area until it was low on fuel and had to return to base.

At the time of the Beaufort incident, the Australians were operating under Macarthur’s Southwest Pacific Command. VD-1 Squadron was operating under US Navy’s South Pacific Command and there was very little or no liaison between the two Commands. Therefore, neither squadron had been informed that they might encounter friendly aircraft while on patrol thus making the likelihood of an incident such as this a very real possibility. The fact that aircraft crews were able to spot the life raft twice in large seas, amply demonstrated the professional expertise and bravery of these airmen. As a descendent of one of the crew, I believe my great uncle Geoff was privileged to serve with such a fine body of men.

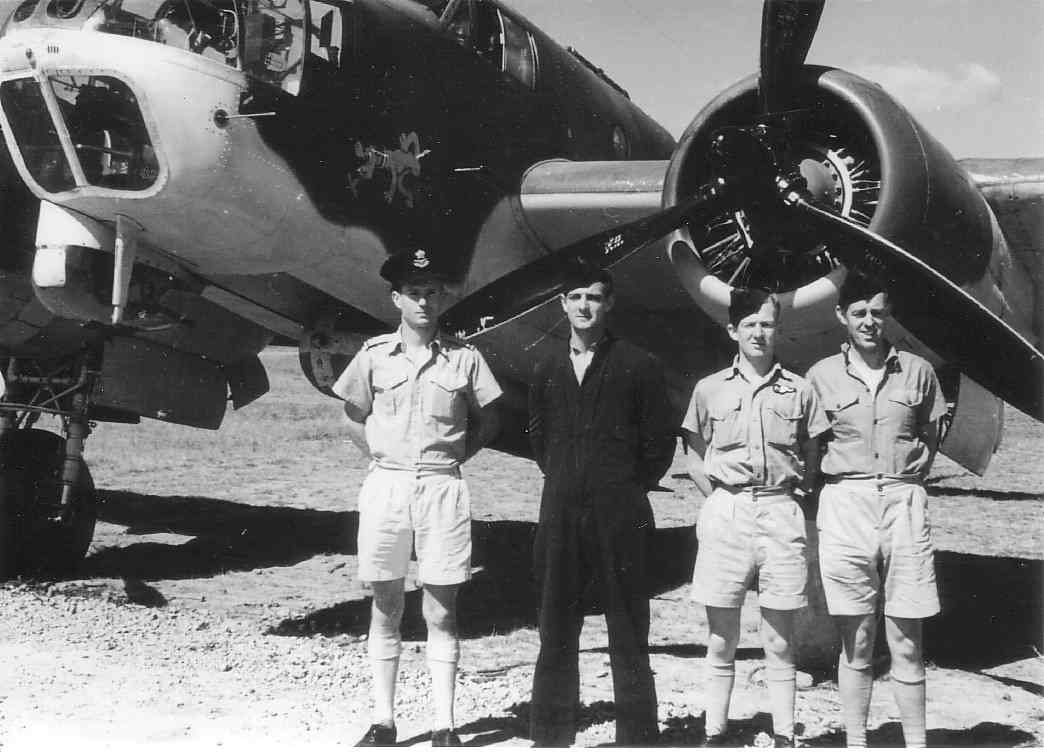

The crew of A9-225 taken during training at BTU in May 1943.

L-R: Flying Officer John Clifton Davis (pilot), SGT George Collins (WAG), SGT William Thomas Brain (WAG) and Flight Sergeant Geoffrey Raymond Emmett (observer).

Collaborative Research – Gordon’s P40’s

I thought I would share some of the following email that was recently received by the group highlighting the collaboration between Gordon B and a Dutch researcher :

Thank you both for the info you have send me on the P-40's and on 120

Sq. N.E.I.A.F.

Some information that may add to what you knew already: The Dutch Catalina's, escorting the Langley were the Y-65 and the Y- 71. On the 27th of February 1942 the Catalina's were damaged by Japanese fighter-aircraft, but both Catalina's could escape to Tjilatjap. On arrival Y-65 was declared unserviceable because of this damage. The Langley was set on fire during the attack of the Japanese bombers. The ship was abandoned and it was sunk by the escorting fighting-ships to prevent it falling into the hands of the Japanese.

The Seawitch arrived safely in the harbour of Tjilatjap. The crates with the P-40's were transported by to Bandung and to Tasikmalaja by rail. Near Bandung the assembly started at dispersed locations near the airfield 'Andir'. Three aircraft have been completed here and these were carried to the airfield. On the 7th of March the first test flights were carried out. In Tasikmalaja more wings than fuselages had arrived. A single aircraft was completed here.

Following the general surrender of the NEI-Army on Sunday 8 March 1942 the destruction of all P-40's was started. Despite detailed reports on destructions, some of the P-40's may have

fallen into Japanese hands. Unknown is the state of the aircraft of 17th Pursuit Squadron that were left behind on East-Java. Also the Japanese in the Philippines captured some undamaged P-40’s. The Japanese probably restored some ten P-40's to an airworthy

condition. Test flights were made on Tachikawa near Tokio and on Singapore.

In March 1943 some were ferried to Rangoon. A Japanese unit in Burma used a limited number of P-40's here for a short time. After VJ-day some P-40's were relocated at dispersed locations in Asia. The origins of these aircraft were never traced.

Thank you for the information you have provided to me.

Editor – Another successful outcome for our research co-ordinator, Gordon on his P40 quest. .

Loss Of Lincoln A73-11 at Amberley on 19 Feb 1948 – Dean Norman

This accident, which resulted in the loss of 16 crew and passengers, was one of the most disastrous in the history of the RAAF.

In fine weather, with rested crews, and what should have been a routine approach and landing after a pleasant transit flight from Laverton, Lincoln A73-11 was rapidly reduced to smoking wreckage with the loss of all on board. The investigation into the tragedy determined that the probable cause was a mal-distribution of the load, placing the Centre of Gravity (C of G) outside the approved aft limit.

The aircraft and crew were tasked to proceed from Amberley to Laverton to uplift some freight plus another Lincoln crew (who had, two days previously, ferried a Lincoln to Laverton for modification action). The aircraft, with two crews, was scheduled to return to Amberley the same day.

Freight details

The freight carried by the aircraft was to have a significant bearing on the accident. A Laverton manifest showed that 2,200lb of freight was carried - excluding personal luggage. Personal baggage carried was estimated to be 400lb.

bases (289 lbs each)

8 gallons thinners

18 gallons methylated spirits

4 gallons chromate thinners 400 lbs

The weather through out the day from Laverton through to Amberley was excellent with little cloud and light winds. During the afternoon, the conditions at Amberley were practically cloudless with a 10-15 kts sea breeze.

For the return trip to Amberley, A73-11 was to captained by the pilot who delivered the earlier Lincoln to Laverton, assisted by the pilot who flew the recovery aircraft A73-11 to Laverton.

The aircraft departed Laverton at 1415 hrs for Amberley. Aeradio position reports were received normally through out the flight, until 1734 hrs, when clearance was obtained to descend from 8000 ft preparatory to the landing at Amberley.

A short time later Amberley Flight Control cleared the aircraft for a straight-in approach RWY 05 at an angle of 45 degrees, turn right to align itself with the runway and commence to lose height on the approach - which appeared to be lower and faster that usual.

The aircraft touched down in a tail high attitude, approximately 300 ft after crossing the threshold. After travelling a short distance, the aircraft then left the ground, rising to about five feet. From eyewitness reports, attempts were then made by the crew to force the aircraft onto the runway but this only resulted in three more bounces.

When about 600 ft from the upwind end of the runway, engine power was applied to make a go around. It is estimated by ground observers that, by this stage, the airspeed of the Lincoln had decreased to approximately 80-85 kts.

The Lincoln was then seen to climb slightly, level out at 100 ft, after which the nose of the aircraft rose sharply to place the aircraft in a climbing attitude of 40 degrees. After a further few seconds, the attitude changed abruptly to a climb of 80 degrees.

With all engines roaring presumably under full power, the aircraft attained an altitude of approximately 500 ft AGL when, with no forward speed, the port wing slowly dropped and the aircraft steadily accelerated until the port mainplane struck the ground in a vertical position. By this time the fuselage was parallel with the ground.

The aircraft caught fire immediately and, although the fire tender arrived shortly after the crash, the fire could not be sufficiently controlled to extricate the crew or passengers. The crash site was 400 yards from the end of RWY 05 and displaced approximately 100 yards left of the runway.

Examination of the wreckage

The engines were clearly capable of full operation. When the propeller dome assemblies from the four engines were removed it was determined that all propellers were in full fine pitch. Additionally, there was sufficient evidence to conclude that all four engines were operating at or near full power at the time of the accident. Badly damaged propeller blades, bent in the opposite direction to rotation, were discovered, several blades being broken.

The empennage, particularly the elevators and associated trim tabs, were closely examined and nothing unusual was found. The flap system appeared to have been operated normally, other than for a minor adjustment between the flap position and cockpit indication.

Distribution of freight

Evidence was obtained from a witness who entered the aircraft at Laverton just before the engines were started. He stated that he saw, aft of the rear door, luggage or freight which was covered with engine covers placed either side of the toilet at a height of three feet. On either side of the fuselage ramp, forward from the rear door to the H-2S scanner, personal luggage was stowed. He did not observe the stowage position of the cylinder blocks or the four gallon tins of dope, thinners etc.

A Merlin cylinder block, identical with those carried in A73-11, was loaded into a Lincoln to determine the probable positions where they could be carried. It was found that it was impossible to stow the cylinder block any further forward than between the rear and main spars. However, the physical effort required and difficulty experienced in getting to this position, made it extremely improbable that this would have been done. Through further load experimentation, the most probable stowage positions of the cylinder blocks for take off at Laverton were found to be:

Similarly, the most logical position to stow the ten containers of dope, thinners etc, to prevent movement during the flight would be forward of the scanner. (Several were found in this position in the wreckage, others being recovered near the rear door).

As no mention was made in the aircraft manifest as to the weight of the personal baggage, it was assumed to be 400 lb, stowed in the aft well.

C of G considerations

The C of G limits laid down for the aircraft were a forward limit of 45 inches aft of the datum and an aft limit 66 inches aft of the datum. With the assumed load distribution the C of G for take off at Laverton would have been 67.4 inches aft of the datum (1.4 inches beyond aft limit). For landing at Amberley, the C of G would have been 71.4 inches aft of datum (5.4 inches beyond aft limit).

Cause of the accident

The accident was caused by a bad load distribution of freight and passengers for the landing, which resulted in the C of G being placed outside the aft limit. This situation occurred principally through the carriage of freight in an aircraft not designed for such a purpose.

It was possible for the aircraft to take off at Laverton and fly to Amberley with the C of G outside the aft limit of 66 inches. It is probable also, that with cruising power, the aircraft could be trimmed for level flight, albeit abnormally tail heavy.

Later, the aircraft captain made a straight-in approach at Amberley. This type of approach can upset a pilot's judgment in making an approach by coming in too low and using power to "drag" the aircraft to the runway. This generally results in a bad landing which in this case occurred, necessitating a baulked approach to be made.

When the undercarriage was retracted for the go-around, the C of G moved 1.6 inches further aft and, with flaps fully down, the engine power was increased to 2650 rpm/+12 psi boost. At this stage the nose commenced to rise; the pilot used full forward stick and trimmed the nose down in an attempt to lower the nose, without effect. Then, probably as a last resort, 3000 rpm/+18 psi boost power combination was used which only further accentuated the already critical situation. The aircraft then became uncontrollable and stalled at a height of approximately 500 ft, with a fuselage angle of 80 degrees to the horizontal.

Carriage of passengers

The carriage of 16 passengers in a Lincoln was in contravention of current orders. All pilots were aware of this order and the responsibility for compliance rested with the aircraft captain.

With the most convenient space for stowage of freight located aft of the bomb bay, it was natural that, if a Lincoln was used for such a purpose, this space would invariably be used, unless the captain was "C of G conscious" and educated his crew to be the same.

Lincoln handling trials

Handling trials were undertaken by ADRU to determine the stability and longitudinal control of the aircraft with various flap settings at different C of G positions. As anticipated, during a baulked approach the aircraft had barely sufficient downward elevator for the crew to maintain for and aft control with:

Subsequent to these tests the following changes were made to Lincoln operating procedures:

Department of Defence Media Release – Funeral Service for crew ED467

Ten relatives of the Australian crew of ED467, the RAAF Lancaster which crashed during a bombing raid over Berlin in 1943, will depart Sydney Airport tomorrow (Friday 11 July 2003) to attend a funeral for the airmen in Germany.

Four Royal Australian Air Force airmen died in the crash, however their remains were not found until over half-a-century later. The crash also claimed the lives of three British airmen.

A full military funeral service, for RAAF and RAF crew of the bomber, is to be conducted on the afternoon of Tuesday, 15 July at the Berlin War Cemetery with the guard of honour comprising airmen from the RAAF and RAF. Chief of Air Force, Air Marshal Angus Houston, will join relatives at the commemoration ceremonies in Germany.

Biographical details and crew photographs may be obtained by visiting:

www.defence.gov.au/media/download/

Feedback:

We value the feedback of the people who visit our website and those who read the newsletter. If you would like to tell us what you think of the website or newsletter,please use our feedback page

Some recent feedback we have received:

Ron Hann from New Zealand wrote:

I had no trouble downloading and printing off the latest issue, including the photographs. Thank you very much. While I don't have any news re Australian aircraft, I can say that one of the R.N.Z.A.F.'s 727's is currently parked at the Deep Freeze area at CHC, all sealed up and obviously not going anywhere in a hurry. I have seen one of the new (to N.Z.) 757's, 7571, and no doubt it, and its mate, when it arrives, will be regular visitors to CHC, as were the 727's.

[Editor’s note: Always glad to hear from aviation enthusiasts across the Tasman]

Graham (Ned) Kelly from Qld:

This site I believe will be something very unique. The ability to catalogue so much data will cause great interest and indeed encourage more and more people to become involved and contribute information which might otherwise languish in drawers and cupboards and never be known about.

Congratulations.

Do you have something for us?

If you have something for the newsletter or would like to submit an article, query or image, please use the following links:

please use our feedback page