ADF Serials Newsletter

For those interested in Australian Military Aircraft History and Serials

ã2004

May 2004

In

this Issue:

· Editors Blurb.

· Comments from the readers.

· Hawker Typhoon 1b: Limited Service in the RAAF. (Gordon Birkett)

· Loss of Phantom A69-7203. (DFS Article via Dean Norman)

· Supermarine Sea Otter Data Plate (Roger Lambert)

· On this Day. (Jan Herivel)

Editor’s blurb

It seems like it was only two weeks ago that I put

together the last newsletter <grin>, hopefully it will keep a regular

schedule until Jan takes over again. It’s a big job to put together the

newsletter and all the detail on the website, it just goes to show how dedicated

Jan and the team are.

Gordon Birkett is taking a break from the P-40

research for this month, putting his efforts into some smaller articles for

your pleasure. I’m sure like me – you are all looking forward to them.

As most of you will also be aware there is some new

anti-spam legislation in Australia. I wont go into any detail or my thought’s,

I will remind you that if you would like to unsubscribe from the newsletter at

any time please go to our website at http://www.adf-serials.com,

select ‘newsletter’ and fill out your details and choose un-subscribe. All

subscriptions and un-subscriptions are done by a human being.

Website News

Grahame Higgs latest Crash

Site page, on Lockerbie is now online…

http://www.adf-serials.com/crash-sites/Lockerbie.shtml

The copyright notice has now

become the copyright and disclaimer notice. The teams thanks go to Dean

Norman and Jan Herivel for putting the words together.

http://www.adf-serials.com/copyright.shtml

Comments/Questions from website visitors and

newsletter readers.

Mirage A3-77

Bob Coppinger is seeking a

photo of Mirage A3-77 to complete his collection. The aircraft was only in

service for a few weeks before being lost in May 1967 with its pilot W/Cd Vance

Drummond, the O/C designate for No 3 Sqn. However, I believe the a/c was on

strength with 2 OCU when it crashed. 37 years of searching have proved

fruitless. Thanks in anticipation.

Mirage A3-23

Noted by Henry Almonte in a damaged state at Masroor AB,

Pakistan, Mirage III 90-523 is stored and used for spares. Date: April 7, 2004,

former RAAF A3-23.

Sabre A94-351, Flying Officer Malcolm Chick

The

following is from Bruce Budd: Many thanks to Bob Alford for his account

of this accident. It fleshes out an account I had from Flt Lt Jim Gilchrist who

was, I think, a controller in the tower at the time. It is no understatement to

say that Malcolm was tall. He stood 6'5" in his socks and I never understood

how he talked his way into Sabres, let alone how he fitted in the Macchi

cockpit. I took him for his first flights in a Chipmunk out of Rutherford and

discovered that a man of his size in the rear cockpit made stall turns

impossible. Prior to his enlistment he had become quite an accomplished glider

pilot. A big man in every sense of the word and still deeply missed.

London - Christchurch Race 1953

Don Felton is trying to piece together the "Entry

List" of the 1953 London - Christchurch Air Race. It had a very

interesting format. I have most of the entries but cannot find information on

the P-51 and Spitfire proposed entrants. I am looking at A68-5,CA-,Mk.20,

VH-BVM as the Mustang. I have no idea for the Spitfire. I would appreciate any

help with any of the entries.

Logbook of Wgcdr A J Esler

Andy Esler, the son of Wgcdr Esler contact the us and has

supplied a copy of his logbook for the team’s use in working on the history of

ADF aircraft. Our thanks go to Andy for his assistance.

Sabre A94-986 Crash 3rd Jan 1968

Paul

Kemp is seeking assistance with respect to above crash in which P/O Mark

McGrath was killed, any help would be appreciated.

RAAF 455 Sqn Hampden’s

And finally this from Shane Mills. Great site, congrat's guys.

You've been a huge help with my modelling. Currently I'm trying to build a 1/72

model of the Hampden flow by Jimmy Cattanach of 455 Squadron. Now, if

someone could tell me what colour the squadron codes and serial numbers were,

I'd be ultra grateful!

Bob Livingstone; As it so happens,

I have a copy of Chaz Bowyer's "Hampden Special" and it has a wartime

colour shot of UB-T AT137 which shows both codes & serial as

Medium Sea Grey. There is a colour drawing inside which shows AN127 UB-C as the

same.

These are on black right up to the cockpit sill, but other drawings show the

same on camouflage.

Whether this was still the scheme on the Russian jaunt, I'm not sure. A

pic

in "The RAAF in Russia" shows a bit of UB-S where the code looks red

& I've

seen another similar in an early "FlyPast".

Thanks Bob and for Ron Wynn for his reply and contribution as well!

Got an idea or some feedback

for us?

Then go to our Feedback page

and fill out the form and send us your thoughts!

Hawker Typhoon 1b: Limited Service in the RAAF

Towards the end of May 1943, three Hawker Typhoons were sent for operational flight trials in the Middle East. 219 Group RAF, who were responsible for finding a lodger unit for these service trials decided finally upon 451 Sqn RAAF. The Typhoon would have been an exciting follow-on to the Hawker Hurricane 11c then operated by the squadron.

The trials were to be

as follows:

·

The aircraft were

to be used on operations whilst carrying out the necessary trials under “sand “

conditions.

·

They were to be

called upon to carry out interceptions etc, in the ordinary way, but were not

to be vectored out of gliding distance from land until such times that they had

completed 100 hrs engine time. This included the time completed in North

Africa.

·

After the trials,

and subject to the trials being a success, the aircraft would be used as fully

operational and could be then vectored outside gliding distance of land.

451 Sqn at LG.106 near

Idku under command of Sqn Ldr J Paine, having been recently withdrawn from

frontline operations, would provide personnel for the tests.

At this time, 451 Sqn

was flying Hurricane IIcs along with a small flight of three “Marker” Spitfire

Mk Vs on loan from 103MU*. The latter were to be used to intercept high flying

enemy aircraft that were, at that time, performing reconnaissance missions over

Alexandria, Egypt. Thus an additional type would have presented some

difficulties with two different types already operated.

*Two of these were BR114 and BR363. (These

“Markers” were specially modified Spitfire Vs that could fly to a height of

40000 ft).

The Trial Organization

All flight line

maintenance for the Typhoons was to be performed by the Squadron, with any

needed modifications to the aircraft being carried out by 103 Maintenance Unit

at Aboukir. The overall command of the

detachment was given to Flt Lt R T Hudson, RAAF Ser#402356 of 451Sqn.

Specialists associated

with the aircraft type were also made available for the trials. These included

Mr. Gale (Hawker Technical Representative), Mr. Richardson (Napier Technical

Representative), and Flying Officer G O Myall RAF Ser#127855 (an experience

operational pilot from the UK).

They oversaw the

assembly of these aircraft with 145 Maintenance Unit located at Casablanca.

With only some three

hours of flying per airframe after assembly, the sand filters were being

damaged.

The cause of the

damage was attributed to the fitting of the Vokes Dry Type air filters in the

UK for the desert trials. The engine, when it backfired, caused fuel to flow

back down the intake trunk to the element, which then resulted in the filter

burning. A new type was ordered from

the UK on the 21st May 43, and was in situ when the aircraft reached Aboukir.

F/O Myall flew both of

these operational Typhoons from Casablanca, in relay, on the 29th

and 31st May 1943, to Maison Blanche. WgCdr Dundas and F/O Myall

piloted the aircraft from there to LG.224 Cairo, arriving on the 3rd

June 1943.

The third Typhoon, EJ906, had suffered a take-off accident, was damaged and required

an engine change before delivery. F/O

Myall returned to Casablanca to fly the repaired Typhoon directly to 451

Sqn. Both Typhoons finally arrived at

Aboukir on the 5th June 1943.

On landing, R8891 suffered a tail wheel burst and DN323 had a hydraulic leak and had also

experienced a solenoid failure for the landing gear fairing doors on take-off

from LG.224.

Pilots were Sqn Ldr Lucas (Hawker Test Pilot)

and F/O Myall.

At the beginning of

June 1943, three new RAF Typhoon pilots were transferred to 451Sqn to participate

in Typhoon trials. They were Sgt. L S Pennell RAF Ser #1425749***, F/Sgt. A H

Davis RAF Ser #1290616 and F/Sgt. T Hough RAF Ser #R69424. These pilots and P/O

G O Myall all were posted to 451Sqn during the next three months.

***Sadly, Sgt. Pennell was later killed whilst

performing shadow shooting over the desert, when his 451Sqn Hurricane flipped

over and dived to the ground on the 18th September 1943.

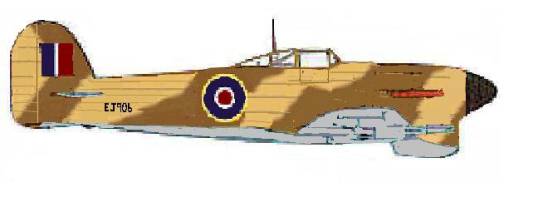

Profile of Typhoon 1b

EJ906 in the Middle East 1943, with black spinner (GRB)

Typhoons of 451Sqn

On the 13th

June 1943, R8891 was readied and on

the following day flown over to 451Sqn at RAF Station Idku where squadron

pilots then carried out several handling tests over the next three days.

On the 17th

June 1943, the aircraft was unserviceable due to the engine attaining 30 hours

thereby requiring a sleeve wear check by the Napier Representative who had not,

at this stage, arrived.

DN323 fortunately had been repaired and flown over on the same day, thus

training continued.

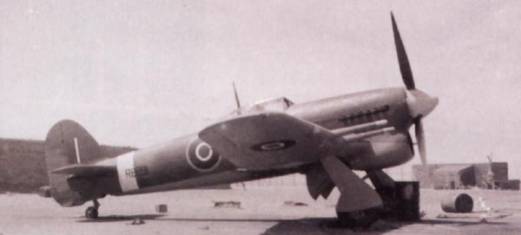

Typhoon R8891

1943 (Bob Livingstone)

Entering into July

1943, the trials involved more and more 451Sqn pilots. The first phase of the operational

simulation came when two aircraft, R8891

and DN323 were detached to LG106 on

the 13th July 1943. Flt Hudson and F/O Myall flew these aircraft

respectively. Various armament testing and simulations were performed.

On separate occasions,

serviceability problems continued on

R8891, such as a tail fairing loss and an undercarriage fairing loss.

Whilst unserviceable

again at Idku with 170 Hours on the engine, an engine change was to be

performed on EJ906 during

August. However there were none

available in the Middle East so permission was sought to hold the airframe as

U/S for spares for the remaining two airframes. Two spare engines were not

dispatched till late August 1943 to 103MU.

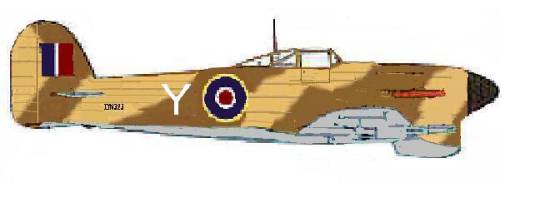

DN323 Coded Y of 451Sqn August 1943(GRB)

EJ906 had also by this time suffered a forced landing, resulting in propeller

and panel damage. The propeller was removed and sent to 111MU for repair. A

suitable spare, of only two in theatre, was despatched to bring this aircraft

back into service by early September 1943.

The trials, having

continuously performed during the past few months, culminated in armament

trials in September 1943. Reports of

stoppages and other armament problems arising from these trials were attributed

to the lack of experienced armourers on that type.

A severe rebuke was

issued to the new commanding officer of the squadron (Sqn Ldr R N Stevens who

had replaced Sqn Ldr J Paine in October 1943) on that matter from the commander

of 209 Group (the parent unit of 451Sqn). This resulted in having Warrant

Officer Peddler being sent to the squadron from the Armament Inspection Unit to

assist in resolving these issues.

These operational trials

continued to the middle of October 1943 with all three aircraft successfully

completing the programme.

The list of pilots

that flew in the 451Sqn Typhoon trials were:

Sqdr Ldr R N Stevens, F/O G O Myall, F/Sgt. Davis, P/O T Hough, Sgt. L Pennell, F/O W Thompson, F/Lt R Hudson, Flt E Kirkhan, F/O J Bann, F/O J Schofield, SqnLdr J Paine, F/O R Bayly, Flt J Trenorden, Flt W Terry, F/O W Gale, F/O S Bartlett, Flt H R Rowelands, F/O R Sutton, and F/O J Wallis.

DN323 at LG106 8-43

The general view was one

of great admiration for the aircraft. The “likes” included the 400mph level

speed at 18500ft altitude, a dive speed of 525mph (Limited), the superb view

out of the canopy and light and sensitive controls.

At this juncture of

history, 451Sqn commenced converting fully to Spitfire MkVc.

The three trials

Typhoons were then ferried to 161 MU on the 23rd October 1943.

This also coincided with the end of RAAF

Typhoon operations.

As for F/O G O Myall,

he departed 451 Sqn on the 15th November 1943 and was temporarily

transferred to No. 22 PTA, pending an eventual return to the UK for a posting

to an operational RAF Typhoon squadron.

This

will be the first of several Limited Service articles with the alternating

P-40E Series and the future Spitfire V articles in our ADF-Serials Newsletters.

My special thanks to Bob Livingstone.

Gordon R Birkett ©2004 Researcher & Co-ordinator for ADF-Serials

Site (Specialising WW2)

References: NAA. [No 451 Squadron] - Typhoon Aircraft (Operations and Instructions etc)

Series number A11305

Unit history of number 451 Squadron - April 1941 to November 1945

Series

number A9186

Loss of Phantom A69-7203

Near Evans Head Qld, 16

June 1971

AT

1813 hrs on 16 June 1971, Phantom A69- 7203 took off from Amberley with a crew

of two, as the lead aircraft in (Carbine) formation, on a navigational exercise

and night bombing on the Evans Head bombing range.

At

1915 hrs, after an apparently normal Navex, the formation contacted the Range

Safety Officer (RSO) for clearance onto the range. Due to a navigational error

the lead aircraft overflew the range while his No 2 joined the bombing pattern

normally.

During

the bombing phase, the No.2 aircraft in the formation suffered a suspected

hang-up of one bomb so a decision was made to return via the alternate route to

base with No.2 aircraft flying as leader.

The

No.2 aircraft reported off the range at 1943 hrs, heading 120 M and climbing

out to 6,500 ft. As he (the lead aircraft) was passing 2,500 ft the RSO

instructed the formation to maintain 1,000 ft due to conflicting traffic

(Cordite formation). The instruction was acknowledged by No.2 and he commenced

a descent to 1,000 ft, turning to port onto a heading of 010 M. No.1, at this

stage, was in the process of rejoining his No.2 on the inside of the turn from

about three miles astern.

While

the leader was levelling at 1,000 feet, he entered a patch of low cloud causing

the rejoining aircraft to lose visual contact. The leader then stopped his turn

until he emerged from the cloud and the joining aircraft regained visual

contact. The leader then resumed his port turn and rolled out on the desired

heading. He then looked behind to see lights, which he thought to be the other

aircraft, at his 8:30 position and very low. Almost immediately the lights

disappeared.

Subsequent

attempts to contact the aircraft were unsuccessful and an immediate search was

implemented. At 0841 hrs the following morning a SAR Orion sighted debris in

the sea that was later recovered and identified to be from the missing aircraft.

Crew details

The

pilot had a total captain experience of 2,536 hrs and held test pilot and

instructor qualifications. He had flown 237 hrs in F-4E aircraft and held an

'above average' assessment.

The

navigator was also assessed 'above average' and had a total of 199 hrs flying

experience on the Phantom.

The

pilot held a medical category A1G201Z1 (aural protection in noise) dated 10 May

1971. The navigator's category was A1G1Z1 dated 15 October 1970. There was no

evidence to suggest any medical condition of either crew member contributed to

the accident in any way.

Aircraft serviceability

The

aircraft was signed off in the E/E500 as fully serviceable for the flight with

the exception of the No 7 fuel tank feeding too early. However, the B4 and Bll servicings

(relating to the oxygen system) were overdue by nine days due to an oversight,

but no evidence could be found to show that these omissions had any bearing on

the accident.

The

aircraft was being operated within AUW and C of G limitations.

Weather

The

forecast weather for the Evans Head area was cloud varying from 2/8 to 6/8

between 800 ft and 20,000 ft with southwesterly winds of 20-30 kts. The

visibility was 10 nm reducing to 2 nm in showers. Eyewitnesses said the night

was very black with nil visible horizon and on the afternoon of the 16th June

and the following morning, several waterspouts were sighted in the area. No 2

of the formation reported the actual cloud cover in the bombing range area to

be approximately 3/8 - 5/8 stratocumulus base 2,500 ft with isolated patches of

lower cloud down to 1,000 ft. Moderate turbulence was evident at 1,000 ft.

Briefing and authorization

After

the normal squadron briefing for the night flying and bombing exercise, the

formation leader conducted a comprehensive briefing with his No.2. This covered

not only the first part of the flight but also the procedures to be observed on

the bombing range and the return flight to base with No.2 as the leader.

The

change of lead was to be accomplished after the aircraft completed the bombing

and were departing the range. No. 2 was to maintain 120 M and initiate a climb

to 6,500 ft at 350 kts. He was then to make a left turn onto 015 M in the climb

so as to roll out on the desired heading above 5,000 ft in order to maintain

separation from the following formation approaching the range from the north.

No.1 was to join up from a 'radar trail' in the climb.

The

sortie was correctly authorised in the Unit Flying Authorisation book.

Description of the flight

The

flight progressed according to plan from take-off until the latter stages of

the bombing detail.

As

the aircraft were completing their last passes, the next formation reported in

and obtained clearance to enter the range. At this stage, they were

approximately 20-40 nm to the north.

No.2

described the following events: 'Once over the target I turned onto 120 M and

climbed to 2,000-2,500 ft, due to low cloud base and slowed to 350 kts. The

No.1 then called "off-safe" with visual contact. Ten to fifteen

seconds later he called "switches off - sight caged". The range

acknowledged and I called "sight caged - switches safe".'

'The

range then told me not to climb above 1,000 ft. I acknowledged and started a

descent back to 1,000 ft. I also started a left turn. During the turn (30°

bank) I entered cloud and No.1 called lost contact. I rolled wings' level and

called my heading of 030 M. Shortly after, I broke out of cloud and he said

"confirm heading 030". I replied "affirmative". He then

said "contact, we're in your left eight o'clock, continue your

turn".'

'I

then rolled left to a heading of 010 M (only about 20° of bank was used). After

No.l's call, my navigator advised me that he had the aircraft in sight and that

he was moving into position.' 'Once I was steady on 010 M, I looked to the left

and saw what I believe was an aircraft in my left 8.30 position, very low on

me. This almost immediately disappeared...'

No.2,

having lost all further contact with No.1, assumed a radio failure in the other

aircraft and alerted all ground stations while he was returning to base,

However, at 2009 hrs when No.2 landed, he was alone, so a search was initiated

for the other aircraft. At 2043 hrs the duty controller noted that No.1's

endurance had expired.

Wreckage examination

Only

minor pieces of the aircraft were recovered, namely:

·

foam rubber

from the fuselage fuel tanks;

·

the right

wingtip;

·

the seat

cushions from the ejection seats; and

·

minor

fragments of metal together with small bits of insulation material.

Examination

of the wreckage indicated the aircraft impacted the water right wing low and

approximately in a five degrees nose low attitude. It broke up immediately as

the foam rubber in the fuselage tanks would indicate. The damage sustained by

the ejection seats' cushions could not have occurred during a normal ejection,

therefore it was concluded that both occupants were in the aircraft at the time

of impact.

Since

the major part of the aircraft was not recovered, no further information could

be gained from the wreckage.

Evaluating the evidence

During

the investigation, the route flown by the formation on the night of the

accident was reconstructed, using two other Phantom aircraft. The pilot of the

rejoining aircraft reported the following observations.

'Coming

off the target in 3 nm trail, No.1 was easily identifiable and my navigator

advised me that we were climbing. I instructed my navigator to obtain a radar

lock-on so he could assist the rejoin by giving me a closure rate.'

'As

No.1 commenced the descending left turn, I attempted to match his angle of bank

and remain in the same plane as his wing. To do this I had to be at a lower

altitude than No.1. Although I had prior knowledge that No.1 was to descend and

there was a good visual horizon on this day, there was no sensation of a

descent when remaining in the same plane as No.1's wing.'

'When

No.1 made the "lost contact" call, I immediately went onto

instruments (at this time I had 30° left bank, passing through 050° M). After

confirming the heading of No.1 as 030° M, I increased the angle of bank to 45°

so I could roll out on 030° as quickly as possible. As I had adequate lateral

separation from No.1 at the time of the "lost contact" call, I knew

that if I paralleled No.1's heading there would be no risk of a collision. When

No.1 went into the 20° left bank turn onto 0100M, I matched his angle of bank

and when I noticed that he was rolling wings level, I rolled into a 30° right

bank turn to effect the rejoin as I was approximately one mile from No.1 in his

low 8 o'clock position. My altimeter at this point indicated 3,000 ft. No.1 was

still at 4,000 ft.'

The

procedure was repeated twice with similar results on both occasions. When the

pilot was questioned later about monitoring the altimeter during the short

period of instrument flying after the 'lost contact' call, he replied:

'No,

because I knew I had sufficient height and as I anticipated that I would have

visual contact with No.1 in approximately 8-10 seconds time, I was more intent

on parallelling No.1's heading and then searching for No.1.'

Due

to the lack of evidence, the possibility of some mechanical failure, ie:

a.

flight

instrument failure;

b.

electrical

failure;

c.

engine

failure; or

d.

air-conditioning

failure

cannot

be discounted. Phantom aircraft have previously suffered flight instrument

failures (ADI) and an air conditioning failure which resulted in the cockpit

filling up with a mist that fogged up the canopy, instruments and the pilot's

visor. However, if any of the above would have happened at height, the incident

need not have been fatal.

In

view of the pilot's previous experience and his reputation for a mature

approach to flying, it was considered that he would not have attempted to carry

out a visual rejoin at such a low altitude under marginal conditions of visibility

if he had been aware of his true height.

The

primary cause of the accident, therefore, was considered to be the pilot

inadvertently flying at such a low altitude that he struck the water. The

probable chain of events could then be reconstructed. The removal of any of the

following events from the chain would probably have averted the accident.

·

The RSO

misinterpreted the call from the approaching formation and believed they were

coming from the south.

·

The RSO,

seeking to ensure altitude separation between the approaching (Cordite) Section

(1200 M), imposed a 1,000 ft restriction on Carbine Section.

·

The leader

of Carbine Section had briefed that he wanted to join up quickly to penetrate

cloud as a pair.

·

The No.2,

who was inexperienced as a leader and who expected advice from No.1, accepted

the altitude restriction.

·

The leader

probably did not hear the RSO's restriction of 1,000 ft or the acknowledgment

due to a possible intermittent radio malfunction, or due to talking with his

navigator, or he did not interpret the call as being for their section due to

the similarity in callsigns.

·

The No.2

began a descending turn from 2,500 ft to 1,000 ft without advising his No.1

that he was descending.

·

When No.1

lost visual contact, No.2 was in thin cloud and No.1 probably expected to

regain contact quickly, Believing he had sufficient height and expecting to see

his No.2 quickly, he may have checked only his heading and bank before again

looking for the other aircraft.

·

The radar

altimeter low level warning light is not effective and was out of the pilot's

field of view.

·

The

navigator was probably engrossed in assisting a radar rejoin, and was not

monitoring the flight instruments.

The

combination of the above resulted in the aircraft being very low, and at this point

there would appear to have been three possibilities,

a.

The

aircraft flew into a waterspout.

b.

A technical

failure occurred such as the failure of the ADI or the air-conditioning system.

c.

The pilot

allowed the aircraft to fly into the sea while attempting a rejoin.

Conclusion

Since

no technical evidence of a malfunction contributing to the accident was

available, the cause of the accident was undetermined.

However,

the probable cause was that the pilot failed to notice the development of a

dangerous situation and allowed the aircraft to fly low enough to hit the

water. Contributing factors to the accident were:

·

the poor

design of the radar altimeter low level warning light; and

·

failure of

the pilot to receive the RSO's restriction and act accordingly.

Comment

Several

lessons can be learnt from this accident.

1.

The safe conclusion of a flight is largely dependent on the proper observance

and compliance with standard radio procedures.

2.

Proper crew coordination as a mutual back-up system is essential, especially

during periods of heavy work load under adverse conditions.

3.

Experience is no safeguard against disorientation.

In this case it is highly probable the pilot was disoriented. He concentrated mainly on keeping the other aircraft in visual contact with no other outside sources of visual cues, and the descent was so gradual that he had no physical sensation of it. His apparently normal radio call 'contact we're in your left 8 o'clock, continue your turn', only a few seconds before the crash, would indicate he was under a mistaken belief of his true height and that he did not hear the RSO's restriction. This accident is more tragic when considering the relatively minor points that combined to cause the loss of an experienced crew and a valuable aircraft.

(Our thanks go to the RAAF’s Directorate of Flying Safety for allowing

the reproduction of this article from the spotlight magazine, also to Dean

Norman for re-typing it for inclusion.)

SUPERMARINE SEA OTTER DATA PLATE

(By Roger Lambert)

In early March 2004, I was visiting my younger brother in Newcastle and he gave

me an aircraft data plate that he had found while cleaning out his back

shed. He recalled that I'd brought it home and that he'd seen the plate

at our (then) family residence in Tyrrell Street but could not remember what

was the original source of the plate. My recollection of its origin was

equally as vague. I did however remember that as a school kid, a mate and

I rode our bicycles from Newcastle to Awaba near Rathmines in the 50s. During

a family outing I'd seen an old biplane in open storage, so we went out to

investigate and photograph the aircraft.

We thought we were photographing a Supermarine Seagull/Walrus. In those days, the airframe was substantially complete, including the tractor engine, although the fabric covered surfaces had seen better days. At the time, I wrote to the Department of Defence seeking information on the aircraft which had the serial, JN200. As you may have gathered by now, it wasn't a Seagull/Walrus but rather one of the two Supermarine Sea Otters that served with the RAN; the forward fuselage of which is now on display at the Australia's Museum of Flight at Nowra. Boys being boys, I can only surmise that the data plate in question 'fell off' this apparently abandoned airframe. The aluminum plate, which is curved as if attached to tubing, is approximately 6.5 cms wide and 5 cms high with attachment extensions either side, is light grey in colour and has the following words engraved in black letters: WARNINGS A/C NOT TO BE FLOWN OFF WATER WITH 'B' TYPE BOMB INSTALLED HAVE YOU REMOVED YOUR HOLDING DOWN LOCKS? The fact that the warning states "not to be flown off water with 'B' type bomb installed" led me to believe that the plate came off an amphibian as the statement seemed to suggest that the aircraft could also operate off land. I wrote to the director of Australia's Museum of Flight, Mark Clayton, in the hope that the museum staff may have been able to identify the plate. With the assistance of the curator, Bob Geale, the plate was positively identified as belonging to Sea Otter JN200.

After all those intervening years, the data plate has now been reunited with the airframe (or what's left of it) of JN200. And just what did the warnings on the plate mean? Steve Mackenzie was able to advise that the holding down locks were the locks inserted into the undercarriage mechanism to stop it retracting (i.e. collapsing the airframe) while in use on the ground. They were obviously removed before a flight to enable the gear to be retracted. Bob Geale was able to advise that from memory the bombs were actually smoke floats used to find and measure wind so that the Observer (Navigator) could keep his navigation plot up to date. In those days there were no navigation aids etc and the aircraft depended on very accurate navigation to find its way safely back to the ship. Also, all radio was W/T using Morse code. Windy should remember this type of aircraft - he use to fly them! He also agreed with Steve regarding the locks - if you trundled down a slip way there is no way you would get the wheels up and definitely no way you could take off. As well, it could be a very embarrassing time if you took off from a carrier or ashore with locks in and had to land in the sea. So there you have it. A little maritime history and a mystery solved. I am just sorry that my mate and I didn't souvenir the entire airframe. We would now have the only Supermarine Sea Otter in the world.

Sea Otter Airframe

On this day, by Jan Herivel

9 May 1927 A2-24 (SE-5A)flown by FLGOFF Francis Ewen fell from formation, entering a dive before crashing into the ground about 600 metres in front of Parliament House during the opening of the new Legislative building. Ewen survided the original crash but later died from his injuries

9-10 May 1943 Point Stuart (near Darwin) bombed by the Japanese

16 May 1943 617 Sqn carry out the Dam Busters raid against targets in the Ruhr Valley Germany

15 May 52 Meteor F.8 A77-373 piloted by PLTOFF Donald Neil Robertson O32536 from 77 Sqn lost on rocket strike in Korea.

24 May 42 Hudsons A16-191 and A16-194 from 32SQN collided in mid air near

Giru, Qld and both aircraft crashed into dense mangrove swamps

Both aircraft collided in mid-air near Giru, QLD and both aircraft crashed into dense mangrove swamps.

30 May 1942 RAAF aircrew participate in the first 1,000 bomber raid – target Cologne, Germany.

Thank

you to Dean and his aircrew losses research, the Australian War Memorial’s

“This Month” and the RSL Diary for dates for this month’s On this Day segment-

Jan

If you have something for

the newsletter or would like to submit an article, query or image, please use

the following link:

http://www.adf-serials.com/feedback/index.cgi